| Brian Froud, Wendy Froud & Terri Windling: making faeries Beth was lucky enough to have an opportunity to meet and speak with Brian Froud, Wendy Froud and Terri Windling during their visit to New York City to promote their joint creation, A Midsummer Night's Faery Tale. This is an excerpt of that interview, as well as portions of their talk given in New York to a very enthusiastic audience.

BD: How did Terri and Wendy meet? WF: Terri and Brian were friends for years and years. We've known each other for about twelve years now. TW: I first met another artist, Alan Lee -- co-author of the original Faeries book -- through my publishing job as an editor in New York ... and I met these two through him. Now we all live in the same little village, filled with people who like to work with myth and fantasy.

BD: What sparked the idea for A Midsummer Night's Faery Tale? TW: It's based on Dartmoor folklore.

BD: So did the story come first or the dolls? TW: The dolls came first, and the story came second. Wendy had already created a lot of the dolls. We had known for a while that we had wanted to make a book together, for years we had talked about the idea, over dinners. When it finally came time to do so, Wendy already had a body of work, dolls that she had put aside with the idea of using them for a book someday. So we had a table full of dolls to work with already before we even started on the book. And it was my job to come up with a story that would incorporate them all. Wendy and I developed some new characters, specifically for the book.

BD: What do you do to refresh your soul? BF: Nature is very important. Especially when doing work that revolves around faeries, because nature is so important to them. TW: The natural areas in Dartmoor are very inspiring, and for me, the desert of Arizona is also refreshing. WF: In addition to nature, I find that going to museums, like the Met here in New York, really helps be clear my mind and focus again, spiritually.

BD: What do you think about faeries being popular again? BF: To me, the popularity of faeries faeries and Faerieland is like the sea, and it's like the tide coming in and out. Sometimes it's out, and sometimes it's in, closer to people. It seems to be in again. TW: It's something that never goes away. It's interesting that the last resurgence of faery art was during the Pre-Raphaelite era, at the end of the last century, so perhaps there's an end-of-an-era aspect to the current popularity of faeries. WF: Or a need for people to believe in something bigger than themselves. Not necessarily a need for religion, but for a spiritual belief, like a belief in Faerieland.

BD: What do you think of the Internet and its impact on readers and books? TW: The chance to reach potential readers is so much greater traditional print mediums. Certainly I find that my own book buying habits have changed -- as much as I want to support my local independent booksellers, dialing up Amazon is so great. You are talking to three technophobes; even though we have Web sites, they are done for us by other people. When my friends from Tucson, Richard and Mardelle Kunz, suggested doing a Web site, I immediately reacted in horror at the thought of doing anything on the computer. But once they showed me the potential of what could be done with art and materials on paper transferred to the Internet, getting mythic art out there to a wider audience, I became hooked. I love providing the material without having to become involved with the mechanics of actually putting it on the Web. And these guys are the same, they don't physically make their Web site, they have someone else do it for them. BF: As an artist I've spent years at the drawing board, where I have a relationship with the page and the paint and my subconscious and muse of inspiration. The bit that's missing is the people who will actually see the work eventually. That happens traditionally through books. When I go out on tour and actually meet the people who read the books, it's wonderful to see how they feel emotionally about the work. But it is quite far removed from the creative process; it takes years for that to happen. TW: And a lot of other people are involved, changing your vision to some extent. The book never comes out exactly the way you envision it, because of the other people involved in the process. BF: So now with the Internet, you get an instant response from people. You get more immediate feedback. What I find really interesting about a Web site is that the audience becomes part of the creative process. They get to see what you are doing as you are doing it; they're allowed to be in on something before it's years later and it's published in its final form. That's exciting, and it's what the Internet can really do. TW: Here's another thing I've enjoyed about having a Web site: When I was in Boston and first founded the Endicott Studio, it was an actual art studio, a physical space, and people could come over and visit. My friends and I would have poetry readings and literary evenings and art exhibitions, but it was limited to people in the area. Now, with the Web site, I feel like I'm able to do the same thing in a virtual way, with the same people, like Ellen Kushner and Delia Sherman, and all my friends who are involved with the Endicott Studio. It's like we have a virtual studio now, and people from anywhere can walk in and see the art and read about the sort of things we talk about.

BD: It sounds like an 18th-century salon. TW: In a way it is, although we don't have the open discussions a salon would have -- we don't have a message board on the site, so there isn't a forum for give-and-take from the public, although there is certainly give-and-take among the artists and writers who contribute to the site. There is a lot of dialogue back and forth on the things we put up there. The discussion aspect is interesting to me and I hope it evolves at the Web site over time.

BD: Wendy, what advice would you give to an amateur puppeteer or dollmaker? WF: If you have a passion for it, stick to it. Get as much training in as many diverse areas as possible and put them all to use doing the one thing you love. That's how I did it. I studied ceramics, graphic design, jewelry making, sculpture, and put them all together.

This concludes the interview. Windling and the Frouds next addressed an eager crowd at Barnes & Noble at 62nd and Broadway, Manhattan.

WF: Well, if you are here, you are probably familiar with Brian's work and Terri's work, but you may not be familiar with me or my work. I'm a dollmaker, and I always have been a dollmaker. When I was a child, my mother read me faery stories, and the ones I was most enamored of were the C.S. Lewis Narnia books. I loved them and I really wanted to be able to play with my dolls and make up new Narnia stories with them, but there wasn't anyplace we could go and buy fauns and centaurs and faery creatures. So I started making them for myself. I made them out of pipe cleaners and old socks and tape, and all sorts of things, anything I had around the house. I've been making them ever since -- I never stopped. I went to art school in Detroit and took sculpture, weaving, ceramics, jewelry-making, and through all those classes I made dolls -- it was what I wanted to do. With all the skills I developed in those classes I made dolls.

TW: Like Wendy, I also grew up loving faery tales, all the old stories of the British Isles and around the world, in fact we grew up with the same faery tale book even though I was in New Jersey and Pennsylvania and she was in Detroit. We both grew up with The Golden Book of Fairy Tales [by Marie Ponsot and Adrienne Segur]. Quite a lot of us in the fantasy field were inspired by that book as children and went on to work with fantasy and myth as adults. I studied folklore at Antioch University in Ohio and also in London and Dublin, then came here to New York and worked for many years as an editor in the adult fantasy book field. I'm a great believer in the importance of myth and faery tales for people of all ages. This notion we have in our modern world that faery tales are just for children is an extremely modern notion. Up until the Victorian times, faery tales were told to people of all ages and all kinds of writers have used them for adult material, such as Shakespeare, Goethe, Tennyson and Yeats. It was in Victorian times that faery stories were pushed into the nursery and went out of fashion for adults, and it was then that they were watered down and turned into the more simplistic stories that we know today. So one of my great missions in life has been to bring faery tales back to readers of all ages, through fantasy novels and also through children's stories like this one which can be read by people of all ages, and we hope enjoyed by people of all ages. After I left New York, and after a few years living in Boston, I moved to a little town in England, on the edge of Darmoor, where Brian and Wendy live -- and also a number of other people who are involved in the myths-and-faery-tales field. Wendy and I had long wanted to work on a book together. When we finally had the opportunity to do so, our hope was to create a book that would not only appeal to people of all ages and all walks of life, but would also convey some of our passion for the folklore that comes out of the countryside in which we live. Faeries are the embodiment of the soul of a landscape, that magical connection between a human being and the love of nature. When you walk into the woods and you have an epiphany, that feeling of nature being so alive and so full of spirit, that's a faery moment! That's what would have been, in ages past, described as a faery encounter. We wanted to incorporate that quality, that experience of walking in the hills of Dartmoor, into our story, both in text and art. Wendy can tell you more about how the art was created. WF: All of the dolls are made out of a polymer clay called Fimo. It's a children's modeling material but a lot of doll artists use it as well. I sculpt the heads and use a wire armature like a skeleton underneath. Whenever possible I make them posable, because I believe dolls should be played with. That was very handy when we started on the book, because we needed to put the dolls in a lot of different positions. I paint with acrylics, and use mostly natural fabrics for the costumes. I like to use silk in all of its various forms, because it dyes beautifully and drapes beautifully, especially in these small sizes. I find that man-made fibers don't work very well for me. When I make wings for the creatures I use a wire armature, iridescent fabrics and paint. I'll let Brian talk about making the sets we used for the dolls, because he was art director for the book. BF: All I said was, "Up a bit? Down a bit? Back a bit?" We call that art direction. We all talked about how the landscape inspired our work but this is the first time we actually physically dragged the landscape into the art itself. We built the sets in our backyard in a shed, and I created these meticulously put-together, beautifully designed sets that Wendy insisted on putting her dolls right in front. I also made tea. And that's about all I did. WF: You brought in John, though. BF: Years ago I met a photographer named John Lawrence Jones. He had come down to visit me, and we were developing a goblins exhibit. I asked for John to work with us on this project, I knew he would photograph all the creatures beautifully. I had been waiting for a long time to work with him again, so it was wonderful to be able to ask him to work on this book. But we realized that we couldn't do this work in his London studio, because we wanted this very naturalistic background. He would come down from London with all of his equipment and we would photograph in little short bursts all through the summer, for about three days at a time. It was quite hard work, because I had to create a set, which we shot in the morning, then we tore it down and I created another one that we could shoot in the afternoon, doing two a day.

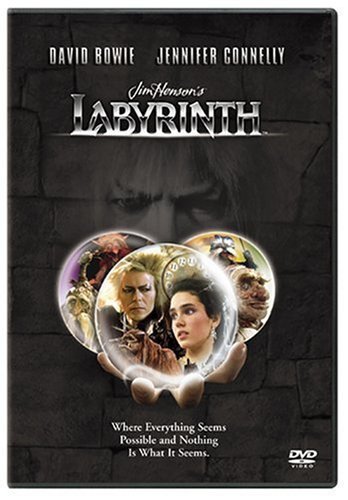

TW: Brian, why don't you tell about how you got into faeries. BF: It happened quite late in life, really. I wanted to be an artist, so I went to art school, and I discovered very early on that people would paint dreadful paintings, but if they had the right words, it was called great art. I always felt that the picture should tell the story, that the information should be right there. I had an epiphany when I realized that everything in the world was designed by someone, by an artist -- things didn't just appear spontaneously. I got into advertising and graphic design, where images contain direct messages. So I changed courses and got into design, which of course is incredibly boring. But waiting for my interview for this course, I came across a book illustrated by Arthur Rackham -- just seeing his drawings of trees with these wonderful dark faces brought me back to the feeling of wonder I'd has as a child, when I was always up in trees. Just seeing the life in those trees of Rackham's reminded me of how I'd felt back then. I started to study folklore and faery tales and taught myself to illustrate faery tales. So I came out of it at the end with such enthusiasm that the college set up a course in illustration. I spent about five years in London illustrating whatever came along. I knew I needed to do my own work, not just commercial work, but I didn't yet know what my own work was. I only knew that it would involve moving back to the country, so that's what I did. I moved to the place where we now live, along an artist, Alan Lee, and his family. In the country, I was immediately inspired by the landscape, and by my spiritual response to the landscape. Every time I looked at a tree or a rock or a stream, I realized that everything had a life to it, had a soul. I tried to paint that, and as I painted, faeries and trolls appeared. It was around that time that I created the book Faeries with Alan. But the first thing I painted, in what I call my mature style, was a troll with a waterfall coming out of his nose. This painting was published on the cover of a book (Once Upon a Time, edited by David Larkin), which is where Jim Henson (creator of the Muppets) saw it, and he asked me to come to New York. It was ironic that I really wanted to move back to the country and I did, but because I felt so much at home in the country, my art blossomed, and the direct response to that was I ended up in New York. I spent six months here, then moved back to England to continue to work on The Dark Crystal with Jim, and that was five years of my life in London. After that we went on to Labyrinth, and then I could finally go home and go back to my love with is to paint faeries.

WF: I was hired because when I moved to the New York with a friend of mine, we had a little exhibition of my work in the loft we were living in. Luckily, Jim Henson's art director came and bought a marionette for Jim for a Christmas present. So I got a phone call early in January asking if I would like to work on this project called The Dark Crystal. I said "Oh yes, please," because I was going to go and be a waitress. It was a really good thing. Brian was brought in to work at the same time, so we met the first day of The Dark Crystal. By the end of the film we were married. BF: The interesting thing was, after having worked with many sculptors on The Dark Crystal for five years and Labyrinth for three, and worked with many sculptors, I consider Wendy to be the finest sculptor for the translation of my work. She is wonderful, I've never found any better. We were at the first showing of The Dark Crystal in San Francisco, and when the film was over, the screen pulled up and showed a Skeksis banquet, with people dressed up as Skeksiss. We had this wonderful meal, the wine was flowing, and we all had a great time. After taking five years of our lives to make the film, we'd all sworn, "Never again." But that night, in the back of a limousine, probably because of all the wine, Jim said "Should we do another one?" and I said "Oh, why not." What we decided in the back of the limousine what that it should be about goblins. We decided to name it Labyrinth, because a labyrinth is a metaphor for so many things. But Jim wanted humans in the film this time, not just puppets, and I suddenly had a flash of a baby surrounded by goblins. Jim liked this idea; he saw a mental picture of it, and I went away and painted it, which was the first production painting for Labyrinth. We had always talked about the baby being about a year old, and when we were coming close to the filming and were about to do a casting call, we suddenly realized that we had our own baby. WF: Well, we didn't suddenly realize it, we knew we had the baby. BF: And he was the right age at the right time, so we thought, well, why not? And we liked the extra money, of course. But the extraordinary thing was that when our son was put in amongst all the goblin puppets, he looked exactly like my painting, which was done much earlier. So that was designing on a grand and cosmic scale. WF: The reason that the baby is called Toby in the movie is because that is his name, and we knew he wouldn't respond to any other name, so he had to be Toby.

Then there was a pause, and they said, "Um, well, I suppose, if you have to do a book about faeries, the only way anybody would be interested is if somebody famous wrote it." So I said, "Fine, find me somebody famous." Six months later I phoned again and they hadn't even thought about it. I went back to the drawing board and carried on painting. I tried again and still met with tremendous resistance from the publisher. Nobody wanted a book about faeries. So out of desperation, I "discovered" Lady Cottington and her pressed faeries. Every time I would tell the story about Lady Cottington and how the faeries would be so inquisitive that they would get really close to the book and she would suddenly slam it shut and squash the faeries, everyone would say "Ugh, how terrible! But I know someone who would like it." No one would admit to wanting the book for themselves, but they always wanted to buy one for somebody else, so I thought, well, at least I'm selling some books here. But it was an interesting philosophical dilemma, because my intention was to bring faeries back into the world, and the first thing I was doing was seemingly killing them off. Once I discovered that they were only leaving psychic impressions and no faeries were actually killed in the making of the book, as was found by the National Society of Prevention of Cruelty to Faeries. So I realized it was OK, the faeries were having a great time. Because of the success of Lady Cottington's Pressed Fairy Book, I was able to do the book I wanted to do, which was Good Faeries/Bad Faeries. I found a great publisher, Simon & Schuster, who had faith in faeries and believe in faeries, so I thank them. So continuing along the faery vein, I'll tell you about some other projects we are working on. We are turning Good Faeries/Bad Faeries into a faery tarot, which we are calling The Faery Oracle, which is going to be wonderful. There is some really exciting new; we have discovered that Lady Cottington's mother took photographs of faeries. Some really bad news, we've learned that Lady Cottington produced a cookbook. Wendy and Terri are working on another Sneezle book, set during the Midwinter Solstice this time. So watch out, there are more faeries on the way.

|

Rambles.NET interview by Beth Derochea 9 January 2000 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!

|

When I moved to New York, I was lucky enough to be asked to come and work on The Dark Crystal and that was the start of my professional career, making puppets. Then I worked on Yoda for The Empire Strikes Back. I wasn't the sole creator of Yoda; I was part of the team that made Yoda. I did most of the major sculpting on it, and I also helped puppeteer. But this is the sort of doll that I make now. This is Sneezle; he is the hero of our story. He's in his tourist clothes. He doesn't usually dress like this, but he has his Hawaiian shirt and box Brownie camera.

When I moved to New York, I was lucky enough to be asked to come and work on The Dark Crystal and that was the start of my professional career, making puppets. Then I worked on Yoda for The Empire Strikes Back. I wasn't the sole creator of Yoda; I was part of the team that made Yoda. I did most of the major sculpting on it, and I also helped puppeteer. But this is the sort of doll that I make now. This is Sneezle; he is the hero of our story. He's in his tourist clothes. He doesn't usually dress like this, but he has his Hawaiian shirt and box Brownie camera.