|

John McEuen, Made in Brooklyn (Chesky, 2016) Joe K. Walsh, Borderland (Skinny Elephant, 2016) By the time Will the Circle Be Unbroken was released in 1972, rock music ruled everywhere, and with an iron fist. Rock critics, then at the peak of their influence, had dispatched folk and roots music -- aside from blues, which few of them actually understood -- to the outer regions of dorkiness. For us dorks it was never less than a struggle, and a usually futile one, to find albums of downhome music in any venue but a heavily stocked big-city record store. Though the folk revival had occurred only a decade before, it felt more like a century. So Circle seemed like something of a miracle, a gathering of a new generation of musicians (directed by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, of which John McEuen was a founder-member) into a Nashville studio with the likes of Maybelle Carter, Doc Watson, Jimmy Martin, Earl Scruggs, Merle Travis and Roy Acuff -- all of them since passed on to hillbilly heaven -- to create three LPs' worth of heavenly hillbilly music.

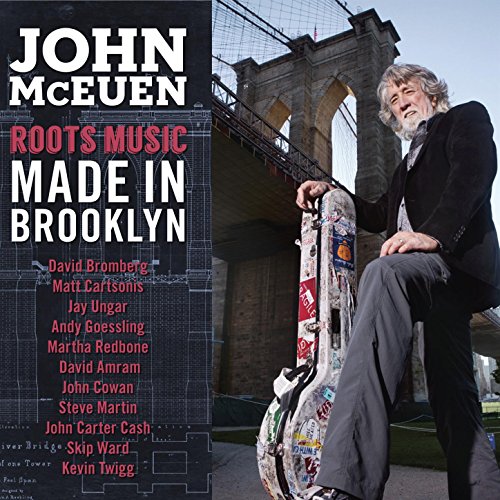

John McEuen's Made in Brooklyn is rather less an event, of course. Where event status is concerned, practically nobody gets more than a single crack. His most prominent companions on this low-keyed modern-folk outing are his contemporaries, comedian/writer/actor/banjo-picker Steve Martin, folksinger/string-wizard David Bromberg, jazz/folk artist David Amram, fiddler Jay Ungar and vocalist/musician John Cowan, once of the influential Newgrass Revival. McEuen, who also produces, plays guitar, banjo, fiddle or mandolin where appropriate. As will surprise no one, the results are pleasing. They're also wide-ranging, the songs and tunes wandering in from an assortment of directions. There is only one old-fashioned bluegrass song, the Flatt & Scruggs evergreen "Blue Ridge Cabin Home" (sung here by Matt Cartsonis) which McEuen credits with showing him "the path out of Orange County" in his impressionable youth. On the other extreme Brooklyn resurrects a couple of songs by the late rock singer-songwriter Warren Zevon, remembered (perhaps unfairly) as the poet laureate of Los Angeles' cocaine-fueled 1970s. "My Dirty Life & Times" reimagines Jesse James as a coked-up player on that scene. The melody steals from that celebrated outlaw ballad, propelled by Martin's clawhammer banjo. I had forgotten the other, Zevon's gruesome, cheeky "Excitable Boy," till Brooklyn brought it back. Whether that's a good or a bad thing is a matter of taste and opinion, naturally. McEuen argues that it's no more repellent than "Knoxville Girl," and he may be right, but personally, I'd take the latter anytime. Another song I hadn't heard in years is the Bernie Leadon/Gene Clark "She Darked the Sun," cut by Linda Ronstadt on a 1971 album. A fine tune indeed, and sung with assurance by Cowan for all its tricky turns. Bromberg and Cartsonis share vocals on Jerry Jeff Walker's "Mr. Bojangles," another song one doesn't mind hearing again, especially if one hasn't heard it recently; once upon a time it was covered enough (early on as a Nitty Gritty Dirt Band single) to wear out its welcome, fortunately not permanently. On the other side "My Favorite Dream" rises from the vaults of the late Nashville songwriter Boudleaux Bryant -- known for Everly Brothers hits and the bluegrass warhorse "Rocky Top" -- to be recorded for the first time. It's an attractive, sophisticated piece that feels as if transported whole from a 1940s nightclub. All of this is wrapped in a warm, live studio sound that plays companionably on the ears.

The man, then, is intensely musical, and Borderland, whose style might be characterized as folk with bluegrass touches, is a beautiful recording. If you are partial to melodies that stick in your head -- and if you aren't, you are probably not among the living and thus not reading these words -- you'll find them in abundance in this space. Well, at least as much abundance as the CD's 38 minutes, which end all too soon, will bear. Be prepared, however, to experience a couple of seismic shocks. One will be in the form of Walsh's bluegrass arrangement of W.B. Yeats's famous early poem "The Lake Isle of Innisfree." (For his rendition Walsh shaves off the first four words of the title.) Now, Irish folklore and music pervade Yeats's writing, and his "Song of the Wandering Aengus" in particular has been set to several Irish melodies ... but bluegrass? For all kinds of reasons this shouldn't work, but Walsh turns a performance so ingenious that the marriage seems an entirely natural one. (Walsh can't resist following it, by the way, with the self-penned instrumental "Bee-Loud Glade," whose title borrows an image from the poem.) Likewise, Walsh startlingly re-envisions Phil Ochs' "There But for Fortune" as the country-gospel "Tramp on the Street," by which I mean he borrows both the waltz time of the latter and snatches of its tune. I think my jaw may have -- literally -- dropped on first hearing this, a blending of two songs (I suddenly realized) on but one theme, the first expressed in secular language, the latter in sacred. What a master stroke. Walsh doesn't do all this by himself, of course. He's blessed with assistance from guitarist Courtney Hartman (of the progressive bluegrass band Della Mae), fiddler Brittany Haas, multi-instrumentalist/oldtime musician Bruce Molsky, banjoist Gabe Hirshfeld and bassist Karl Doty. Congrats all around.

|

Rambles.NET music review by Jerome Clark 29 October 2016 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!  Click on a cover image to make a selection.

|