|

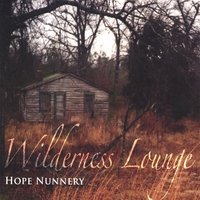

Hope Nunnery, Wilderness Lounge (independent, 2007) From the very first cut, there can be no mistake: Hope Nunnery is not just another sweet-voiced singer-songwriter. "All My People" launches Wilderness Lounge with a fierce, androgynous wail, calling up "A sign, a sign, souls beware / Cries from the black swampy darkness... / Flesh is dropping from the bone... / Flesh and bone will be as one." This is the dank, haunted world of "Oh Death," expressed in the doom-laden tones of Dock Boggs and Ralph Stanley, only with the promise of heavenly respite after the suffering of the soul and the rotting of the body.

Not all of the material is self-composed, but the atmospheric distance between her astounding "Watch Man" and the venerable 19th-century hymn "Sweet Bye and Bye" (with our mutual friend Jim Watson singing harmony) is slight. Some of Nunnery's songs could have been written decades ago, some a century or more ago. Some have the resonance of 1930s country music, and other songs feel like mountain ballads or downhome blues. Nearly all are imbued with all-consuming guilt and prayed-for redemption. And yet they feel timeless, not like period pieces at all. The emotion they deliver -- in composition, voice, arrangement -- will knock you off your feet as surely as a bolt from the blue aimed straight to the heart. Perhaps this is the sort of art no younger woman could create and carry. In one of her songs, Nunnery, who lives in Manhattan but grew up in rural South Carolina, refers to herself good-humoredly as an "old gal singer" -- she was 52 when Lounge was recorded -- and she draws from a deeper well of experience than most other, less-seasoned writers and performers do. This, rather incredibly, is her first album. It's as good as (and, perhaps because of her greater years, more consistently realized than) John Prine's legendary first album from nearly four decades ago. A good part of the album's success owes to Steve Tarshis's production. Though a photograph shows the two of them posed in front of upright flattops, Nunnery provides only vocals, with Tarshis playing acoustic and resonator guitars, with some tasteful percussion and background singing here and there. Tarshis, whose deep schooling in traditional American music is manifest, assembles like-minded players to handle fiddle, banjo, accordion, mandolin and bass duties. The production could not be improved upon; Tarshis is almost psychically attuned to Nunnery's vision. He steps forward once to handle lead singing on his own splendid "Trouble is My Rider," inspired in more ways than one -- as anyone who has heard it will instantly recognize -- by Harry and Jeanie West's long-ago version of the traditional "Rake & Rambling Boy." Wilderness Lounge is an exceptional, even extraordinary, recording, more than just another successful effort by a talented artist. It's no impressively accomplished approximation of the real thing, either. It is the real thing, and you should not miss it.

|

Rambles.NET review by Jerome Clark 5 July 2008 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!

|