|

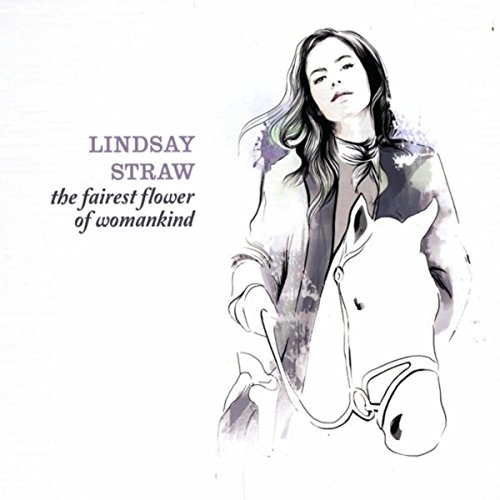

Lindsay Straw, The Fairest Flower of Womankind (independent, 2017) various artists, Classic English & Scottish Ballads (Smithsonian Folkways, 2017) Between 1882 and 1898, under the byline of Prof. Francis James Child (1825-1896), the first professor of English at Harvard University, five volumes of The English & Scottish Popular Ballads, 305 in all, saw print. The title notwithstanding, at least some of these ballads were not intrinsic to the British Isles. Known in other languages and variants, some had migrated from elsewhere in Europe and even North Africa. Child relied upon published sources, and most entries are supplemented with multiple versions, plus discussions of their origins, histories and meanings. My own library hosts the most recent edition, edited by scholars Mark F. Heiman and Laura Saxton Heiman and published by their Loomis House Press in Northfield, Minnesota, between 2001 and 2011.

From the early 1600s into the early part of the 20th century, ballad texts were hawked on broadsides (sheets with printing on one side) and sold in stores, at fairs and markets, and in other public settings, including public hangings. Some of these undoubtedly predated their associations with such street literature. Usually, though, a hack employed by the publisher penned the lyrics to simple verse formulas and set them to familiar, easily sung melodies; thus, the music of broadsides typically was older, even much older, than the words. Only a small minority of broadside ballads entered folk tradition, but when they did, they sometimes took up residence for an extended period. And over the years they underwent the same process of alteration as their medieval counterparts. Fittingly, what may be the most antique song on Smithsonian Folkways' splendid collection is the only one on Classic English & Scottish Ballads to be sung by someone who was not American: the late English folksinger Ewan MacColl. "Thomas the Rhymer" relates a supernatural legend attached to Thomas of Erceldoune (1226-ca.1297), kidnapped by the Queen of Elfland and subsequently rewarded with prophetic powers. It is a strange and riveting tale, though not frequently recorded; I am aware of two other versions, one from 1974 by Steeleye Span (Now We are Six), the other from 2016 by Andrew Calhoun (Rhymer's Tower), though I'm sure revivalists have recorded others that have escaped my notice. As a general principle MacColl's singing style wasn't for everybody, but his unaccompanied reading in this instance is undeniably stunning. (If you're interested, I discuss the larger context of the ballad within the Scottish fairy tradition in my 2010 book Hidden Realms.) Otherwise, the singers are Americans, mostly presenting the songs in their North American incarnations. They range from source musicians such as Horton Barker ("The Farmer's Curst Wife"), Warde Ford ("Andrew Batan") and Dillard Chandler ("Mathie Groves") as well as revival stalwarts like Pete Seeger ("Lady Margaret"), Mike Seeger ("Lord Thomas & Fair Ellender") and Jean Ritchie ("Lord Randall"). The performances are divided between the purely vocal and those accompanied by one or more stringed instruments. At 21 cuts, with an hour and 13 minutes' worth of some of the richest, most intriguing songs in the English language, Classic is not just a wonder but a bargain, too.

While Classic roams the ballad landscape, incorporating a range of narratives and themes, Lindsay Straw, a young woman from the Boston folk scene, focuses on the stories in which female protagonists triumph in one fashion or another. Other themed ballad overviews have examined history, violence or the supernatural, so what Straw does on The Fairest Flower of Womankind feels fresh. Certainly, there is no shortage of strong ballads about women, and not just ones slain by psychopathic boyfriends, usually named Willie for some reason. Along with the occasional unaccompanied number, Straw sings the songs in nicely imagined guitar arrangements, here and there augmented by fiddle, harmonica or harmonium courtesy of guest artists. If the influence of Frankie Armstrong is sometimes apparent -- which as far as I'm concerned is all to the good -- Straw delivers the narratives in wry, straightforward, not-too-sweet style. While the musicality is striking, it does not draw attention to itself. She properly draws the listener's attention to the stories. It is gratifying that these magnificent old ballads live on, as if in defiance of this culture of amnesia and instant obsolescence. It's inspiring, moreover, that they're done as assuredly as they are in this young artist's voice. While the most recent date to the 19th century, Lindsay Straw carries them into the 21st in fine form.

|

Rambles.NET music review by Jerome Clark 27 May 2017 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!  Click on a cover image to make a selection.

|