| William Styron: a dose of his war

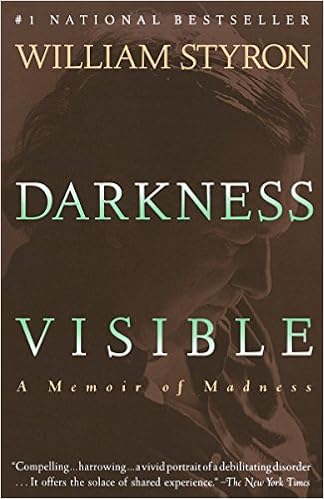

But the author, 72, finally made it to F&M -- as a scholar instead of a student -- where he treated more than 250 people to a novel in progress. Styron's fiction has never failed to incite reaction by delving into issues of ethics and history. His pen has touched on a great slave rebellion in The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Holocaust in Sophie's Choice and his own flirtation with depression and suicide in Darkness Visible. The decline of literacy and the general public's lack of interest in reading is "a crisis in our time," Styron said. "The written word is not always a matter of total respect." But the bluff, grandfatherly good-humored writer held his audience in thrall with his vivid recitation from an unfinished, semi-autobiographical manuscript about soldiers preparing to invade Japan. "Here we are, a happy band of word lovers," he said. "I am prepared to give you a dose."

The setting for his story is Saipan, the island in the western Pacific where the U.S. invasion force waits. It is 1945, and Styron's first-person narrator calls it "the time of the ambulances." "A stream of ambulances came with their freight" -- maimed and bloodied soldiers carried from battlefields at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. The young platoon commander is reading a book of verse and listening to Miller and Dorsey -- small tastes of home -- but is distracted by the sounds of passing ambulances and the screams of wounded men. "Poetry was no remedy for such a sound, so I shut the book and lie there in a numb trance," Styron read. "I, too, might have suffered these wounds and miseries."

The moving narrative gave the audience an up-close perspective on the soldiers' fear and despair. As Styron read, students flinched at unfamiliar images of war-time gore, while some older heads in the crowd simply nodded. Overwhelming the bloody narration and subtle hints of homoeroticism is the narrator's dread of a visit to the island's psychiatric unit, where a good friend is lodged. He can only imagine the horrors that drove trained soldiers into catatonia and battle fatigue even before seeing combat. Styron, or rather his narrator, feels close to that condition himself, and he daydreams about a sterile seclusion from fear. He ponders the Tokyo firebombings which claim civilians and soldiers alike. The soldier becomes a "cheerleader for utter destruction." If it will stop the horror, he says, "then bombs away." The heart, conscience and capacity for pity are lost in the reality of war. The passages Styron read at F&M were part of an unfinished short novel "about this horrendous situation of young men on an island, paralyzed with fear, as we all were, thinking, 'This is the end.'" The A-bomb gave them all "a new lease on life." "It was life. And we who went through that had a vision of inimitable peace the minute we set foot back in the United States," Styron said. "Of course, we didn't have peace. Six years later I was back in the Marines for the Korean War." But that, he said, is another story.

|

Rambles.NET interview by Tom Knapp March 1997 Agree? Disagree? Send us your opinions!

|